The Architecture of a Gamble

Mapping the AI Value Chain

A while back I talked about producing an analysis of the AI industry. I’ve put together something pretty extensive, but on reflection, I’ve decided to put it out in multiple parts. This post today functions more as an outline, where the following posts will dive more into each layer of this stack and then finally look in more depth at the macro-economic aspects.

Introduction

If you look solely at the headlines in 2025, the artificial intelligence industry appears like a single coordinated effort with unprecedented wealth. We see trillions of dollars in valuation, feverish construction of data centers, and a frantic race for silicon. But to view AI as a single, unified industry is to miss the mechanics of how capital flows, and how that creates stability in some places, and precariousness elsewhere.

The reality is a stack—four distinct layers of value, each operating under different laws of physics and economics. At the bottom is the concrete reality of energy and silicon. At the top is the promise of productivity through software. Between them lies a complex web of subsidies, speculative bets, and “soft dependencies” that are challenging the laws of traditional business.

At the base, capital is being aggressively spent on lower layers of the stack, to both meet current and expected future demands from higher layers. Higher layers are operating speculatively, bringing in capital through speculative investments and running at a loss, in expectation of unprecedented future revenue growth.

This creates a commercial stability gradient that decreases as you move up the stack, where revenue covers less of investment and depends more on future growth.

The Compute Supply Chain (Layer 1) is paid first. While future demand, and thus revenues cannot avoid a dependence on the higher layers, they are also selling hard product today, and being paid well for it. As businesses, they are more stable, though you should be careful about translating that commercial stability into assumptions of stock price stability, which assume both high demand and high margins, neither of which is certain.

The Operational Infrastructure (Layer 2) is mixing revenue from higher layers and cash flows from existing business to fund purchases from Layer 1. This layer is competitive even before AI, and AI’s influence may make it more commodity-like and more competitive. Investment is speculative, but structured for stability.

The Intelligence (Layer 3) is precarious. Only a fraction of spending is covered by revenue; the remainder is funded by investment capital and debt, driven by high optimism. While capital costs are not as high as Layer 2, they are still high, and so are operational costs. Almost all this goes to Layer 2 as current revenues. Cash flow is negative and dependent on ongoing investment, while also being highly competitive.

The Application (Layer 4) is diverse, and where value is realized. Other layers depend upon this to bring the revenues that pay for capital and operational costs. The risk here is an Attribution Gap. Real value is created, but measurement it is difficult. This leaves uncertainty if users will pay enough to justify the massive investments at lower layers.

This structure creates an unstable relationship. If spending in the Application layer doesn’t expand rapidly, the investment optimism funding the Intelligence layer could dry up, leaving a critical gap in the revenues needed to pay back investors and meet the ROI expectations of the infrastructure below.

An interesting exception to this structure is application layer companies can be more commercially stable than Layer 3 companies. If they demonstrate their own value to customers, and decouple via negotiation with Layer 3, they could reach profitability before Layer 3.

As a diverse layer, many different outcomes should be expected, with some companies successfully navigating their own path and others failing. Also, while this shifts more everyday, a reasonably significant part of this layer (25%) is direct OpenAI/Gemini/Anthropic user subscriptions, coupling that revenue to Layer 3.

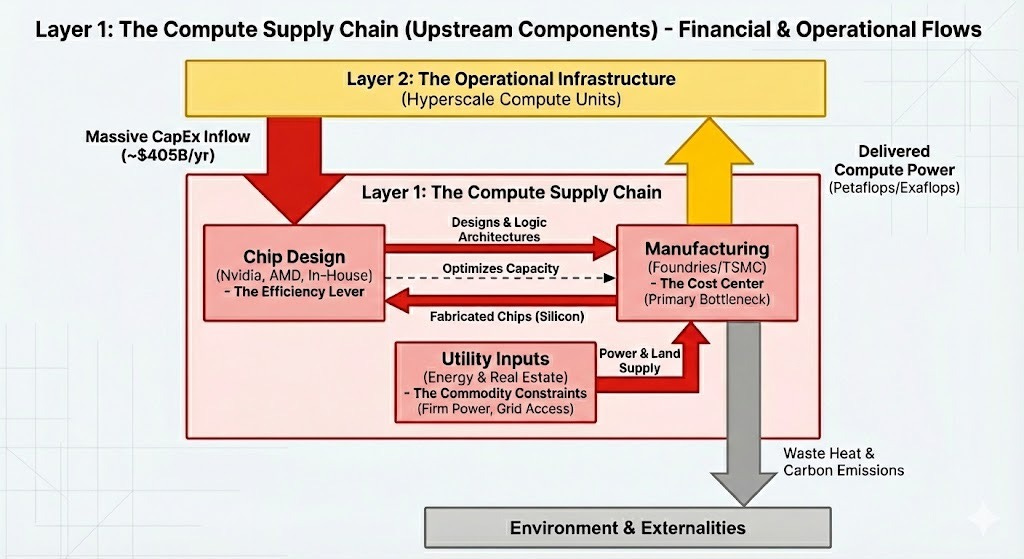

Layer 1: The Compute Supply Chain

The foundation of the AI stack is not code, but the “hard” reality of atoms: the physical and logical inputs required to create intelligence. This layer is dominated by the high capital cost and expansion timelines of chip manufacturing, which feeds into the economics of the entire industry.

Foundries, such as TSMC, represent the hardest constraint and the largest capital commitment. TSMC alone is projecting $40-42 billion in CapEx for 2025. This creates a “pervasive price” because chip manufacturing costs factor into most other costs. Training needs chips, and inference needs chips.

While foundries deal with the brute force of fabrication, chip designers like Nvidia and AMD operate the Efficiency Lever. Their economic role is to maximize the usage of scarce foundry capacity. However, the lines here are blurring. Hyperscalers like Amazon and Google are increasingly designing their own silicon—Trainium and TPUs—to optimize their own costs, effectively internalizing the supply chain.

Surrounding this is the often-overlooked constraint of utility inputs: energy and real estate. All compute requires reliable power, making grid access a key determinant of land value.

One of the advantages for NVidia and TSMC’s is that chips are being sold today. TSMC may have high CapEx, but for 2025 has $120 billion in revenues, and $40 billion net income. NVidia has an even more appealing 2025 forecast of $115 billion net income and revenue of $200 billion, with only $6 billion in capital expense.

$115 billion in income doesn’t justify a $5 trillion market capitalization, it has to grow to support that, but as a business there’s no lack of commercial stability. It’s also a mistake to look at NVidia’s favorable position, and imply stability for the entire AI industry. That just means the rest of the industry is paying for NVidia, it doesn’t mean the rest of the industry can afford to.

If demand continues to grow this layer’s hard constraints—manufacturing capacity and power availability—will give it pricing power. If it flatlines, that’s lost, but investments will still be repaid. Demand would have to pull back significantly to translate into internalized losses. Stock prices could be volatile, and bad choices there could cause individual investors to experience losses, but that’s partly the nature of stock markets in general.

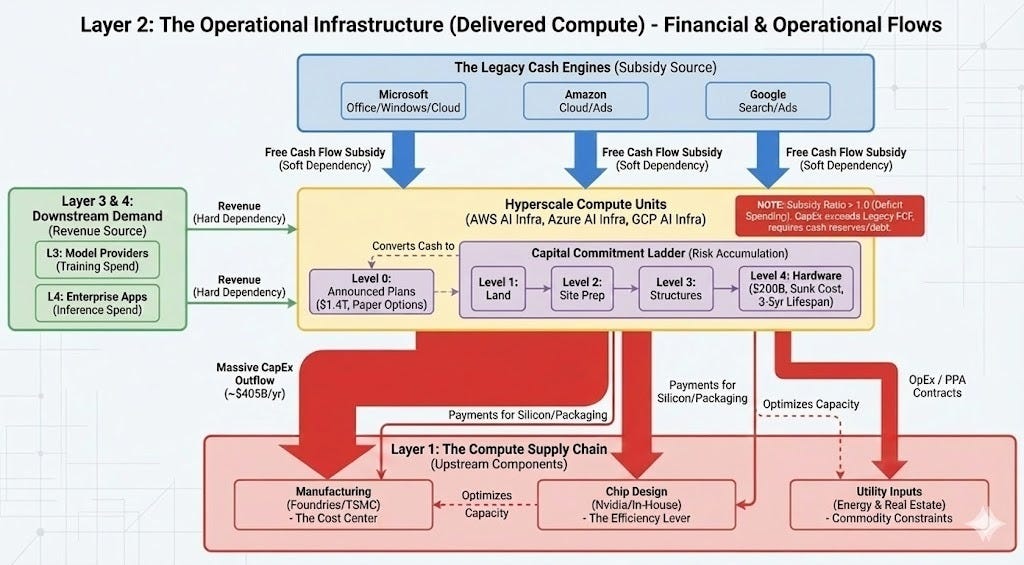

Layer 2: The Operational Infrastructure

Disclaimer

Now is a good time to remind you that while I work at AWS, this is a personal Substack. Opinions are my own.

Sitting directly above the supply chain is the Operational Infrastructure, defined by the delivered compute. This layer efficiently deploys chips using existing cash flows, and keeps them operational. Very CapEx dependent, but so far, self-financing. The primary examples are the hyperscalers: AWS, GCP and Azure. These companies are absorbing the massive AI infrastructure costs using cash flows from mature, non-AI businesses like search and retail. A full accounting must consider smaller providers and private deployments.

We are witnessing a classic Installation Period: a rapid infrastructure overbuilding driven by FOMO and strategic necessity. Similar to the fiber-optic boom of 1999-2001, physical assets are being deployed ahead of proven demand. While this typically leads to a capacity glut, such a glut is eventually beneficial for the economy, as excess capacity drives costs down and subsidizes the next wave of innovation.

In my follow-up, I’ll dive into

The CapEx numbers from each entity

The CapEx breakdown by type (chips, land, buildings, etc.)

The differences between projected CapEx, announced CapEx, commitments, and actual spending.

The revenues from supporting training, inference.

Layer 3: The Intelligence

The third layer is the speculative core of model providers. The current core are those with frontier model programs, such as OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Amazon, Meta. While this layer captures the public imagination, its economic footing is far more slippery than the infrastructure below it.

These companies face a brutal paradox: they provide the cognitive engine for the entire ecosystem, yet “intelligence” itself is trending toward a commodity.

In this high-velocity environment, legacy advantages are fleeting. A leader can be dethroned by a single release cycle from a competitor. Unlike the infrastructure layer, where assets have a useful life of years to decades, a frontier model can depreciate in months.

Changes in position happen often. At the moment of writing, December 2025, OpenAI is not the leader, and it’s open to debate between Google Gemini and Anthropic Claude Opus/Sonnet as the momentary leader. You’re only as good as your latest model on the frontier. Niches are developing, on a cost basis and use case basis. But even here, a niche can be swallowed by the new frontier release, or lost to a new release targeting the niche.

A long term advantage here would have to be founded on execution: creating effective models cost-efficiently. The most optimistic view is that a recursive feedback loop emerges. If AI improves model architecture via an algorithm loop, or AI improves chip design, these create novel impacts.

A chip design loop would be slow and shared, as a new chip design would have to go next to manufacturing, and dependent on chip designer intellectual property. An algorithm loop could be faster, and self-contained. While this area is fairly speculative, it’s a foundational one to how many model providers think, at least at the fringes.

Financially, this layer is precarious. Revenues are not large enough to pay for past training costs, so companies are still unprofitable. Internally they face a revenue gap where growth projections often presume exponential conversion of free users to paid users, without a proven reason for that assumption. They also are dependent on the realization of many other revenue sources from the application layer.

In my follow-up, I’ll dive into the revenues and expenses at this layer.

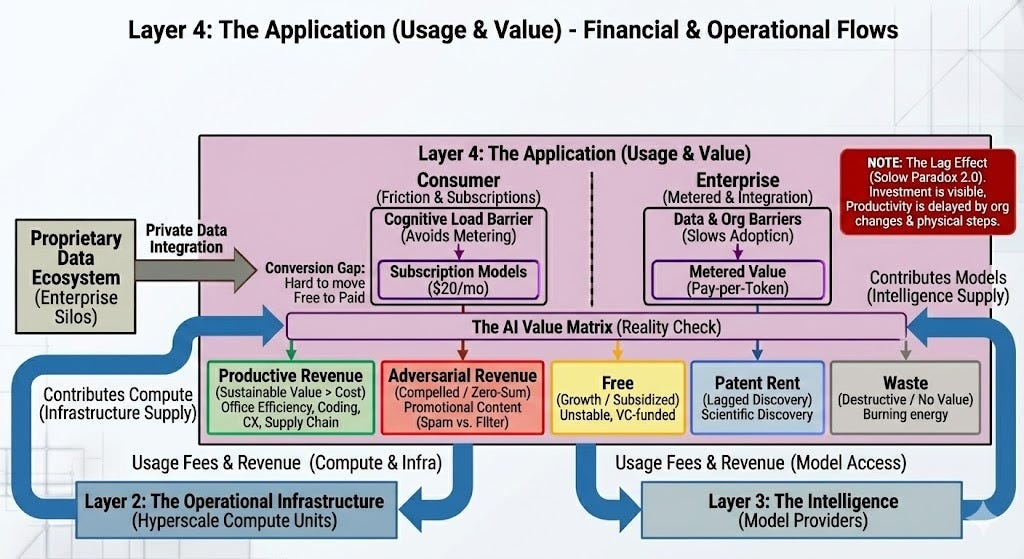

Layer 4: The Application

The most critical disconnect in the modern AI economy sits at the very top: The Application Layer (Layer 4). This is where the rubber meets the road—where enterprises and consumers actually use AI to solve problems.

In a healthy market, the revenue from this top layer would cascade down, paying for the models, the servers, and the chips. Today, however, that flow is a trickle compared to the flood of investment rising from the bottom. We are facing an attribution gap. While AI creates real value—writing code, summarizing documents, speeding up research—measuring that value is notoriously difficult.

Besides the attribution gap, there are other frictions, an implementation gap, an integration gap, and an adoption gap.

Before users can make use of the potential capability of a model, for a specific purpose, they often need an implementation. Consider coding and coding tools as an example. Before coding tools, like Kiro, supported spec driven development, the ability to use models for this purpose was challenging. The same goes for earlier advancements, such as generating tests. Sure, you could in theory have done this with a chatbot and a lot of copy and paste, but that’s not good enough to make it practical. The implementation takes theory to practical. The number of implementation gaps, between what the best models could in theory do, and what users have good tools to do, is growing faster than it’s shrinking.

Even with an implementation, another type of gap is an integration gap. Intelligent decisions depend upon access to relevant and current data. Data does not automatically become integrated. For good reason, data has to go through the process of integration, where security, quality and structure have to be resolved. And it’s not just data, but also actions, which quite reasonably have a yet higher bar for proper integration.

Finally, there’s the adoption gap. Even when a tool or process is available, and integrated, skepticism, awareness, and habits often mean it’s not used. There’s a relation back to the attribution gap here too, as the inability to attribute value helps fuel skepticism.

The attribution gap, and the other frictions slow down both the actual implementation, and the creation of revenue. This results in a lag effect. The industry is currently in a race to see if revenue can expand fast enough to justify the valuations before the Installation Period speculation cools.

In my follow-up, I’ll dive into:

Two types of revenue, consumer and enterprise, and their different frictions. A preview here; this is changing rapidly and the enterprise is becoming more important.

Different types of value-revenue relationships, and their importance to delivering social value from usage.

Tasks that can create revenue, and their relationship to value.

Macro-Economic Effects

I’ve written about this a bit in the past…

In my follow-up I’ll dive into:

How the current state of the AI industry feeds into the overall economy

How different types of revenue have different effects on the economy separate from the effects on the AI industry.

Conclusion

The bottom of the stack is being paid for by upper layers. The largest contribution comes from the internal investment by the infrastructure layer. But this is reaching its limits. Some additional capital is being supplied by the intelligence layer, in the form of external investment spent on training and inference in excess of their own revenues. Finally, the application layer is bringing in revenues. Those revenues wouldn’t be less than enough to pay back CapEx to date, and would be trivial in comparison what would be needed to pay back projected CapEx.

Thus, the current internal and external investment is absorbing the costs of infrastructure in the belief that the application layer will eventually catch up. If projected CapEx is to occur, new sources of investment will be necessary, likely through debt and larger amounts of equity financing. A drop in optimism could cut these plans short and create market volatility.

This is not necessarily a disaster; it is a historical pattern. We are deep in what economists call an Installation Period. Much like the fiber-optic boom of the late 1990s, we are overbuilding infrastructure ahead of proven demand. This is a feature, not a bug, of technological revolutions. This overbuilding is inflationary and chaotic, driven by Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) and strategic necessity.

The eventual result is almost always a capacity glut. It’s not a foregone conclusion, and pinpointing the timing is a much harder prediction than the simple occurrence. If you forecast on potential value only, and ignore the attribution, implementation, integration and adoption gaps, it’s almost certain to occur.

In theory, good forecasting can forestall or avoid a glut. In practice, there’s usually at least one market participant that’s constitutionally inclined to pursue the most optimistic interpretation, and FOMO pulls others behind this wave. Lagging behind too much when optimism prevails risks being left out with a struggle to regain position. In other words, playing it safe isn’t always safe.

When optimism finds its failing point stock valuations correct violently. But for the economy at large, this is the “turning point.” A crash in the cost of intelligence would reduce the barriers of an attribution gap, spawning a burst in adoption that needed to unlock a Deployment Phase. With past revolutions this is where the technology becomes cheap and reliable enough to be woven into the fabric of everyday life.

With AI, we might wonder if the model of the railroads, which experienced serial corrections, could fit better as one correction is not enough to close all of the potential gaps.

For now, the AI economy is a structure supported by massive financial scaffolding. The heavy lifting is being done by legacy profits and speculative investment, all betting on a future where the friction of adoption disappears. The question is not whether AI adds value, but whether the application layer can expand quickly enough to catch the weight of the massive infrastructure being built to support it.

Next in this Series

In the coming posts, we will peel back the layers of this stack one by one, examining the specific data and market dynamics driving the Compute Supply Chain, the precarious economics of Model Providers, and the reality of Enterprise Adoption.

A very thought-provoking article, Ryan! Can't wait for the rest of the articles on this topic.