Delayed Effects and Dangerous Unpredictability

The Real Risk of Tariffs

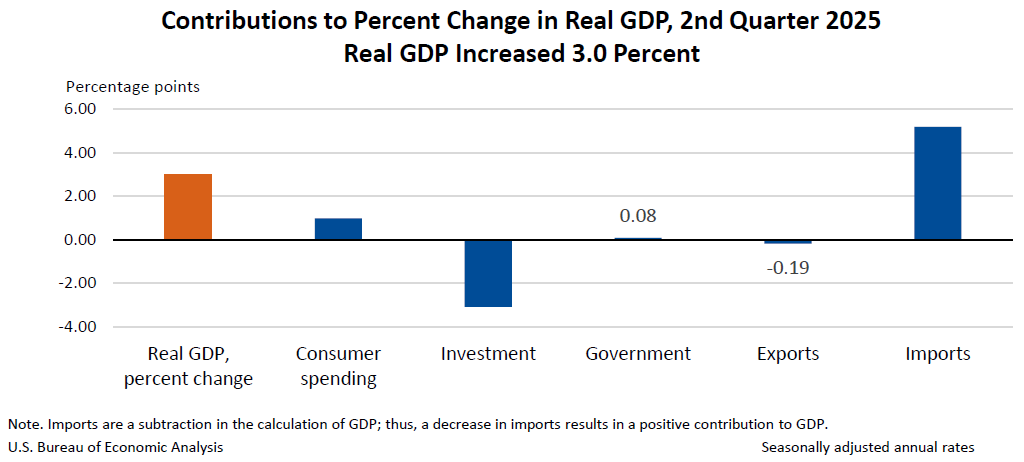

Economists have warned of tariffs' impact on the US economy. The stock market has dropped when policies were announced, recovered when policies partially undone, or delayed, and then reached new records, while continued new announcements and implementations occurred.

If your main mechanism for judging the different claims is by looking at your own personal situation, you’d likely be uncertain that anything bad was going to happen. Unfortunately, that’s not a good way to judge how an economy of 340 million will behave.

There is an effect of tariffs, and the business uncertainty they have created. While it may be somewhat masked, the masking has limits.

How tariffs affect businesses that produce goods

In a simple world, where a tariff was established without all the reversals, delays and uncertainty, the effect on business largely depends on what the businesses do, and what options they have to make changes.

For a business involved in manufacturing, they would be affected by inputs and outputs. In terms of outputs, if they have a foreign competitor that has the same output taxed, it gives that business an opportunity to raise their prices or get more market share, at least in the long term.

In the short term, local business has to react to what foreign competitors do. If those competitors keep the same pre-import price, the post-import price increases. Local business then can increase their prices, and gain more profit. Alternatively, if local businesses have the capacity to produce more, they can maintain their current prices and find willing customers who choose their product over the foreign competitors due to the relative price change.

It’s also possible their competitors choose to reduce their pre-import price. This inherently means less profit, unless they can force their suppliers or workforce to take less for their inputs or labor. If foreign competitors take less profit, this either will lead to less ability to invest long term which will reduce their market share eventually, or to the existing investment becoming negative value.

In the short term, there would be limits to expanding production, but with some predictability about the future, a business that expects to have a competitive advantage would invest in expanding. If a local manufacturer knows they’ll make more profit per item at the same price to the consumer, they can price lower to attract more business and be sure that extra production capacity won’t go to waste.

The timing of this does matter. It doesn’t make sense for a local producer to undercut their foreign competitor until they can produce enough to take additional market share. Until that point, the local producer would be better off maintaining a higher price, accumulating more profit, and using that profit (and the additional access to capital it enables) to invest in more production. Only after that investment adds more production capacity would they undercut their foreign competitors' prices.

Foreign producers will want to continue to use their existing capacity. They’ll have less incentive to invest in more capacity, but in the immediate sense, there’s no reason for them to reduce prices. If they assume the tariffs will remain in place, they would want to capture what profit they could until the local producer undercuts them in a way that makes the existing capacity unprofitable to operate, at which point they would idle that capacity, and possibly take more final measures, such as selling equipment or parts, declaring bankruptcy, etc.

Again timing matters. One set of decisions, continued operation or idling, depends on the realities of today. Another set of decisions affords a more complex set of options:

New Investment

Maintenance with no investment

No maintenance, and no investment

Dismantling operational capacity

These decisions depend on future expectations. If the competitive advantage looks favorable for the future, new investment makes sense, either to capture any growth in demand, or to force a competitor to choose option (3) or (4). If competitive advantage looks even, option (2) makes sense. If the reality is a competitive disadvantage, you’ll choose between (3) and (4) based upon how fast your competitor expands and the prices they set.

If a competitor can't meet all the market demand, a company might continue selling with its existing equipment. However, the most profitable move could be to let a shortage happen and dismantle operations (option 4), especially if the costs of maintaining idle equipment are high. In other words, as a company produces less, its competitive disadvantage can worsen, forcing it to dismantle its operations even faster than its rivals can grow to fill the gap. If not, the company would likely continue to produce and sell until its competitors capture the entire market through lower prices and greater supply.

Effect of tariffs on inputs

In addition to all of these considerations about the effect of tariffs on outputs, there’s also the consideration that an input may have a tariff applied. Assuming there is a local producer for that input, that full story about the balance between foreign and local producers will play out. During that time, the input’s price would initially increase. The simplest logic assumes the initial price increase would be equal to the tariff rate, but it could be less. As expansions and contractions take place, the price would reduce from this increased price. The most likely settling point is still higher than the initial price.

While it is possible to craft a story that ends up with the final local price being lower, it would depend on specific equilibriums. Then there is the counter point that you could end up with shortages that cause prices to exceed the original price plus tariff. Anyone who tells you such situations are probable without a very detailed set of data is making overconfident predictions.

If you’re a local producer that both has inputs increase in price and has their foreign competitors affected by tariffs on the output product, timing your investments becomes more complicated. For one, you probably don’t have enough information about the business of your potential suppliers to know what their optimal pricing model would be. For two, they may not either. For three, even if they have the information to choose an optimal pricing model, they may be run by less than fully rational individuals, or hope that their competitors have less than full information.

Most businesses must have a lot of confidence in their own competitive advantage or the growth potential of their industry before they commit to investments. In general, they’d prefer to risk their customer’s experiencing a shortage, and thus being able to raise prices, then to risk having unproductive investments.

We often make the mistake of only thinking about high growth industries' business models. In those industries, early investments are somewhat defensive. Beyond creating customer loyalty, there are also scale advantages. The producer that reaches a certain scale first captures that part of a competitive advantage. Dislodging them from this position at the apex of growth is more expensive than an early lead, as exponential compounding of those costs applies. As such, in a high growth industry everyone wants an early lead.

But industries in which growth is minimal, flat or contracting, this preference for investment doesn’t exist. Even if a competitor invests first, the scale advantage is trivial or non-existent, and the amount it costs to invest early and later are equal or roughly equal.

It’s in this environment that a country imposing a tariff should worry about the possibility of shortages. The foreign producers may no longer see the local market as worth exporting to, and yet the local producers may have favored being conservative about their investments to the degree that their capacity expansion isn’t available until after a shortage is experienced. In a liquid global market, a local shortage would be resolved by bidding up the pre-import price. However, markets aren’t fully liquid, and so it could be left unresolved, due to contracts and agreements and the simple nature of shipping delays.

How tariffs policies create business uncertainty

In a long term, static economy, reasoning about the effect of tariffs is simpler. In a more dynamic model, or during periods or transition, it becomes more complex, and timing must be factored in.

When Trump announces a policy, reverses the policy, reimposes the policy at half the initial level and then adds another layer on top, this more complex model adds yet another layer of complexity. The effect of uncertainty is a greater degree of delay for investments, increasing the probabilities of high local prices or local shortages, which would lead to even higher local prices, in addition to the actual shortage.

Risks of Oversimplifying

At times it’s appealing to try and apply our own personal experiences with money and finance to economic reasoning. For example, when you think of businesses delaying investments, you might think of it like a personal decision to buy a new car or keep driving the old one. If you don’t spend on a car today, you save that money, which you retain as potential to buy a new car (or something else) later.

For an individual business this is a little bit similar. They do have the complexity of building relationships, organizing operations, to worry about. Still, a company with $100 million in the bank has a lot of potential saved up.

Where this analogy breaks down fully is at the level of a national or global economy. Despite all the talk about imports and exports, most national economies have the majority of their production and consumption locally consumed and produced. For example, about 89% of U.S. consumer spending is on domestically produced goods and services. When you or a business saves money, you can later exchange the money for a good or service, with the most minimal of restrictions. But national economies have limited options to use currency to demand goods or services, and a global economy has no options.

An economy can store value by stockpiling produced goods or raw materials, but the outcome of delayed investment usually doesn’t translate into stockpiling. Rather it tends to mean less circulation of money. In many cases that would cause less employment, and labor can’t be stored. If a person is unemployed in 2025, you can’t get them to do two years worth of work in 2026.

At an economy wide level, if one business doesn’t invest, another may find it easier to get the loan necessary to invest. But when investment is lower across an entire economy, the result is mostly waste that can’t be recovered.

The connections between businesses

The combined effects of uncertainty and actual tariff costs affects US businesses. Despite braggadocio claims that foreigners would pay for tariffs, the evidence so far is that Americans are bearing them. So far a lot of it is landing on American businesses. Some people might consider that a win, a take down of profitable US corporations. But ultimately that’s a shortsighted view, and ignoring the composition of American businesses.

The problems are (a) this is unlikely to continue for long, (b) affects many smaller businesses, and (c) many Americans are invested in those corporations.

One of the reasons this won’t continue? Some of those costs are being buffered by pre-tariff stockpiling. When those stockpiles are gone, businesses will have harder decisions to make. They could have raised prices, earning a small profit for being wise enough to stockpile, but they weren’t forced to. In the future, the choice of raising prices will not represent a decision to forgo a small one-time profit, but may represent a choice to be unprofitable generally. Businesses that aren’t profitable eventually stop being businesses. If that’s the case, the pattern of bearing costs will end and consumer prices will rise.

Even if the change in costs is small enough to only reduce profit, rather than invert it to a loss, these costs aren’t borne just by large corporations, many are smaller businesses. Those business investment plans are altered by a change in cash flow.

Finally, remember that Americans own quite a lot of those corporations, and that changes to their profitability will lower rational valuations. Those corporations also do a lot of investing too. In the end, one thing must decline, either investment or dividends, and in both cases this should translate into a lower valuation.

The risks of delayed effects

I worry that a set of delayed effects that have masked the developing effects of tariffs and inconsistent policy will all land at the same time. The effect here is far more worrisome than the stock market's initial reaction to the tariffs. That reaction was based on expectations, and expectations are easily corrected by a course change. The wave of effects that have been working their way through our economies layers, are not so easily reversed.

Investments that businesses put off to build stockpiles, and due to uncertainty meant real work wasn’t being done. We finally saw the effect of that in a revised jobs report. It’s not simply that the stockpile is gone, it’s that the stockpile itself had costs, and we’ve largely been missing those costs as we take advantage of the stockpile. But when that’s exhausted a new price must be paid, in addition to the loss of investment. Even if all tariffs are permanently reversed next week, those effects will continue to show up.

Businesses, large and small, that use profits or a cash cushion to absorb costs will make that clear in quarterly statements, or in more personal ways for smaller businesses. Even if all tariffs are permanently reversed next week, those costs remain. If they continue, they keep growing.

We’re deep enough into the tariffs that foreign shipments are disincentivized by high tariff rates, and yet businesses have not invested in replacing that supply. This creates a balance sheet problem if they’ve lost their cash cushion while waiting, and now finally see enough certainty to make investment worthwhile. In theory this can be fixed by credit, and investment can start and eventually these local producers would have more market share. But there’s a looming shortage between these points. We can’t really avoid those shortages where they are lurking. Maybe I’m wrong and such shortages aren’t lurking, but I’m not sure who could give you a reason to be confident in that.

Even if all tariffs are permanently reversed next week, arranging new supply will come with many complications. Supply contracts can take time to restart.

And then there’s the businesses that have had their production costs increased by higher input prices, or will have higher input prices. Those businesses have a hard set of choices. They can raise prices. If they do that alone they lose customers. But if all businesses in an industry come to the same conclusion, they may just shrink the market. If the market shrinks then the industry has to scale back costs or lose money.

In a competitive market, in the long run, a business only has one option, to raise prices. If they operate at a loss, they’ll go bankrupt. If they operate at a lower margin, they’ll lose access to credit and be unable to make investments. That will have different effects depending on the market's potential for growth.

In a growth market, not making investments will cause market share to drop. At an individual business level, that would be destructive, making raising prices a better option than accepting lower margins (which are sometimes already negative in growth industries), and lower investment. If, counter to that, it does make sense to accept lower margins, the result is the growth industry transitions to a period of no growth, which brings effects to the wider economy.

In a stable market, investments are less frequent, but can still be necessary to perform maintenance. Loss of access to credit can then force such businesses to shrink, albeit slowly as deferred maintenance slowly reduces efficiency and capacity. Capacity reductions can cause a loss of scale advantages, raising per unit costs and thus forcing the increased price vs. lower margin tradeoff to begin again.

In the end, the only real option for businesses that were at an equilibrium before, is to raise prices. It’s tempting to imagine that most businesses are out of equilibrium, and that profits are high enough that none of these effects are triggered. It’s a hard story to disprove in any given moment because finding the equilibrium for individual businesses and industries is quite difficult. For the most part, we don’t have a better mechanism for discovering this than the actual conduct of markets. If you knew a stable equilibrium other than what markets discover for themselves, that information would enable you to make a lot of money by outsmarting the markets. While it’s not impossible, history tells us this is far more difficult and rare than overconfident predictors make it look.

Conclusion: Cascading Risks and Lasting Costs

The true risk of tariff policies lies not just in their immediate costs, but in their potential to create a cascade of lasting economic damage. The uncertainty generated by shifting trade rules discourages business investment, a loss of productivity that cannot be easily recovered. As this article has detailed, these policies create a ripple effect:

Delayed Investment: Businesses postpone crucial investments in new equipment and capacity, leading to long-term economic waste and a higher risk of future shortages.

Supply Chain Fragility: As foreign supply is disincentivized and domestic replacement fails to materialize, supply chains become brittle and prone to disruption.

Absorbed Costs and Rising Prices: While businesses may initially absorb the costs of tariffs through lower profits or cash reserves, this is not sustainable. Eventually, these costs are passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

These factors create a fragile economic environment. Unlike a temporary market fluctuation, the structural changes caused by prolonged trade conflicts, such as lost investment, atrophied supply chains, and bankrupt businesses, are not quickly reversible, even if the tariffs themselves are lifted.

These changes can develop with less visibility, below the level of awareness that drives market prices. But when that lack of awareness is shattered, a course change is insufficient to undo the change in expectations that awareness brings. The economic consequences, therefore, will persist long after the policies that created them have changed.